The metaphysics that undergirds Reclaiming Art is a form of weird realism. By “the Real,” I don’t mean the consensus world that can be analyzed by social scientists, measured by scientists, or delineated by idealist philosophers. Nor is it the “real world” worried parents and school counselors refer to when they give career advice to reckless teenagers. That world is an idea in our heads, a partial picture framed by reason and the notion of causality: “Everything has a cause, and whoever knows the cause can predict the effect.”

It was the Scottish philosopher David Hume who argued that, contrary to common belief, causality has no logical necessity. The real reason we expect a coin to fall to the ground when we toss it in the air isn’t that it logically must do so but that we have made a habit of believing that what goes up must come down. In truth, there is no reason whatsoever why specific effects must follow from specific causes. After all, it is perfectly possible to imagine a world where tossed coins simply float up into the ether, never to return. The fact that they haven’t in the past does little but explain our habit (mere habit!) of expecting things to keep going the way they have been until now.

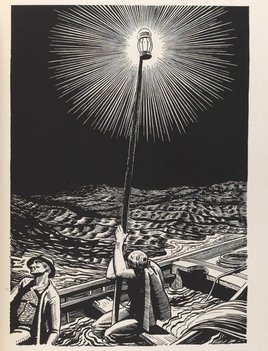

So in reality, the outcome of every coin toss is unpredictable: maybe it will come down, maybe it won’t. (NOTE: I realize I'm being flippant here, but bear with me.) The Real inheres in this unpredictability, this maybe. It points a strange, unknowable order that hides behind our preconceptions, habits, and judgements. In fact our habits— all the armature of culture — form a kind of veil to protect us against it. The Real is the interzone where anything could happen, all things are possible and no amount of expert knowledge can enable us to predict what might come next, or even what is actually going on in a given situation. In the book I qualify it with the term “radical mystery” — radical because it goes right to the root of things. “The dream hath no bottom.” This mystery isn’t a problem that has yet to be solved; it is naked reality itself, as experienced when the veil falls away.

The Real is the excess that makes every Weltanschauung we super-apes construct necessarily limited and ultimately inadequate. We never get to the bottom of things. We never arrive at the final truth. There is always something that eludes us. The concept of the Real is predicated on the notion that reality exceeds the capacities of human reason — absolutely.

Compare the way people conceived the cosmos in the Middle Ages with the way we conceive it today. Here are some pretty incommensurable differences. Some might argue that the medievals were dead wrong about the world and that we today are right. But then, medieval people laughed at the naivety of the pagans who dwelt in metaphysical ignorance before the birth of Christ. Nor is it very difficult to imagine that people living three or four hundred years from today will laugh at us for our current beliefs. As Richard Grossinger puts it in Dark Pool of Light, “the universe is overdetermined.” It is too rich, too complex, too deep, too alien for the human mind to grasp in its totality. The gap between what goes on in our cogitations and what actually is is unbridgeable, even as it moves, shifts, expands, and contracts. That gap is the Real.

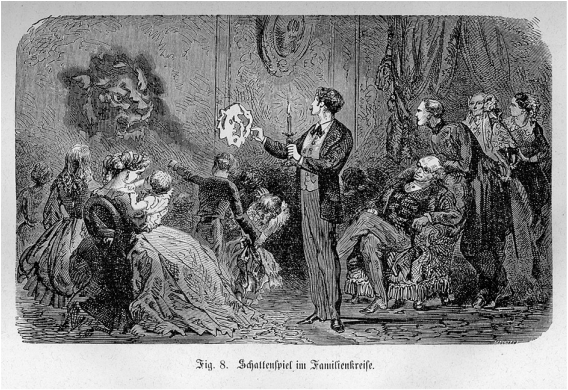

Picture the following scene, a cartoon cliché. You’re standing on a darkened street corner at night. Suddenly an immense form appears on the brick wall ahead, a terrible, monstrous shadow cast by something coming around the corner. When the creature casting the shadow finally appears, it turns out to be an inoffensive kitten. The whole thing was a trick of the light.

Now, according to our conventional way of seeing things, the part of the scene where “truth" is revealed is the moment when the kitten shows itself. It’s at that point that you realize that the monstrous shadow was an illusion, that what was actually coming towards you was in fact the most mundane, benign, and knowable of God’s creatures. Yet if we entertain the concept of the Real I’ve just outlined, things change. The moment you were closest to “truth” — the moment you were most in touch with the Real — was in the interval during which you did not know what you were looking at. For then the monstrous shadow pointed you to a zone of potentiality with which you are not familiar, an open space between the little world you think you know and the big, real, unknowable world. What I mean to say here is that it is in moments of uncertainty, when we don’t know what we’re looking at, that we are epistemologically aligned with the true nature of existence.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed