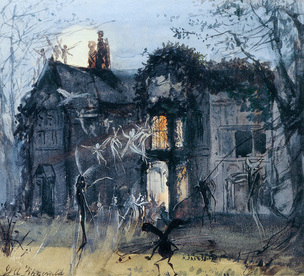

"The Old Hall: Fairies by Moonlight," by John Anster Fitzgerald, circa 1875

"The Old Hall: Fairies by Moonlight," by John Anster Fitzgerald, circa 1875 The poem's narrator is reflecting on the mansion in which he lives and plans to die:

We knew for long the mansion's look

And what we said of it became

A part of what it is ...

In the future, the narrator muses, the house as an entity will include all he has said and thought about it. Which is to say that the experiences through which an object manifests to us are constitutive of the object itself as an autonomous entity. Objects take shape in experience (human experience being just one variety), but they do not exist “within” our experience, “within” us as subjects; rather, each experience of an object expands that object, allows it to express its being, objectively.

All of the elements that make up the mansion exist on their own, experienced or not: Stevens is no idealist. But the elements can only constellate as a mansion — a homely one for the narrator, a haunted one for the children of the future — through encounters with human beings who are themselves similarly constituted.

In other words, all things substantiate themselves in encounters, in meetings, as Martin Buber wrote. It is through human experience that a house learns to be a house, that it learns to be homely or haunted as the case may be, just as it is through the strange sentience of the house that we become home-dwellers, which is to say human beings. A person coming upon a house is an encounter, but it is an encounter between equals at the primal level.

A new house feels cold and dead because, as an object, it hasn’t yet learned to be a house. It is a house in form only, which is to say a design, an intellectual ideal, the concept of a house given material consistency. When we say that a house feels lived-in or homely, we are saying something about the house itself, not just about our impression of it. The house has come to life as a house; it knows itself as a house. It has a genius loci, a spirit of place, indistinguishable from it.

Later, having been abandoned and then occupied anew, the mansion in the poem will hold as part of its being all of the memories formed in conjunction with it. My guess is that nine times out of ten, this is what we mean when we speak of ghosts. "Children," Stevens writes, "[will] speak our speech and never know,"

Will say of the mansion that it seems

As if he that lived there left behind

A spirit storming in blank walls ...

The mansion confronts the children with all of its past that is real and, in a sense, ever-present. Stanley Kubrick's film The Shining reveals this with a force equal to Stevens' poem in the form of the Overlook Hotel.

***

ADDENDUM -- Some readers have expressed confusion at my statement that Stevens' poem suggests the absence of interiority.

I don't mean that thought, feeling and imagination do not exist. What I mean in these notes is that our "interior world," what appears to we modern people as a private realm that is closed off from the world of objects, is not actually closed. Our thoughts are already out there in the world, objects among objects or forces among forces.

The idea is that mind is an aspect of the universe, not the exclusive property of private subjects (Descartes). The universe includes psyche; it doesn't oppose it, nor does it exist in a separate order from psyche. In the poem, the narrator's thoughts about the house do not belong only to him: they belong also to the house, which preserves those thoughts as part of its own being. And they belong to the children of the future who will inhabit the house. After all, if those children "will speak our speech and never know," it follows that the narrator himself speaks the speech of other beings without knowing it. "There is no interiority" means that there is no disentangling subject from object.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed