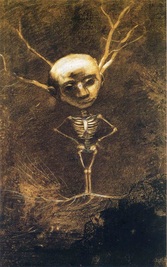

Odilon Redon, The Spirit of the Forest, 1890

Odilon Redon, The Spirit of the Forest, 1890 Materialism is the belief that the world is made up entirely of physical “matter,” and that this matter somehow gives rise to subjective minds when organized with sufficient complexity in the form of nervous systems. Idealism goes the opposite route, arguing that in fact there is only mind, and that matter exists only as a content of mind, that is to say, as a representation for a transcendent subject. For the true idealist, there is nothing to reality but subjective perceptions: the universe is "inside" consciousness and not the other way around, as materialists would have it.

Materialism has been dominant since the end of the nineteenth century. Today it remains something of a default view even though a growing number of people are dissatisfied with its insistence on a universe made up of dead stuff, not to mention its total failure to account for conscious experience. Idealism, for its part, is relatively unpopular among university types but extremely popular in the culture at large (e.g., so-called New Age thought).

I think Segall is right to say that both materialism and idealism “as polemical positions are themselves misunderstandings of or partial perspectives on a more complex truth.” The question, which Segall readily discerns, is whether this more complex truth is in any way knowable in rational terms. At the end of his short but rich post, Segall challenges the mainstream association of mind with reason and logic, suggesting that there is “a certain madness at the core of the Intellect, something unruly, chaotic, creative...” As soon as we entertain the thought that mind is not fundamentally or primarily rational, new avenues open up to philosophical thought. Philosophy becomes less inquisitive (or at least less inquisitorial) and more creative, experimental. Its traditional concern with formulating truthful propositions can take a backseat to a revived interest in creating truth in a manner analogous to art. In other words, instead of mastering thought to rationalize (and thus absolutize) the human world, philosophy can follow thought into new, non-human territories, and potentially expand our world beyond its actual confines.

What ontology could support such a view of the intellect? Certainly not materialism or idealism, which both hinge upon an extreme form of rationalism. The most promising inroads, in my view, are being made under panpsychism, which David Skrbina defines as a meta-theory about the nature of matter and mind rather than a “polemical position” in itself.

Panpsychism holds that matter exists just as materialists say it does, but adds that matter includes psyche—that all matter is in some way alive, experiential, or sentient. Everything, all of nature, has an “interior,” an imaginal dimension. In the spirit of Pan, the wild horned god whom the name of this philosophical school evokes, Nature has two manifestations: there is an external nature that we perceive in the form of physical forces, and an internal nature that we perceive as image and psyche. Nature, in short, includes thought, emotion, imagination, soul.* Matter is not merely material but energetic as the physicists tell us and psychical as the depth psychologists hold.

What I like about panpsychism is that it is a totally immanent prospect: it does not require one to posit a conceptual substance that transcends the universe that plants and animals inhabit. Materialists and idealists require just such a transcendent substance—an absolute—that lies behind the phenomenal world, generating it. Under both philosophies, existence is necessarily relegated to the realm of illusion. For materialists, the universe is really a blind play of quantities, totally inaccessible to the mind which, for its part, merely apprehends these quantities under the guise of a qualitative mirage. Materialism offers us a world devoid of meanings, purposes, or values; psyche is epiphenomenal, a kind of fume on the surface of the mathematical marshes of pure quantitative relations in space-time.

As for idealism, it admits of nothing but subjective representations. For idealists, the qualities we perceive in the universe are all that exist—there are no real things possessing those qualities. There are no objects, no events, only images that we as "naïve realists" take to be objects and events. Life is literally a dream, the theatre of which is either your own personal mind if you’re a solipsist (the most honest, as well as the most odious idealist position) or the mind of God if you’re willing to grant other people the privilege of also having a mind (for then you need to explain the existence of the common world in which these various minds interact).

If, in total contrast to this, panpsychism shows promise, it is because it allows one to affirm that the world we experience is real, that it exists as it seems to and requires no transcendent substance in order to do so.** Experience is neither a dream nor a hallucination, but a direct engagement between living beings in a living cosmos.

Throughout his career, and more emphatically in the latter part of it, Gilles Deleuze said that our most pressing task today is that of finding a way "to believe again in this world." For several centuries now we have denied the world its reality; we have espoused an anthropocentric view in which humanity is the arbiter of all values, including the value of existence itself. The results of this world-denying attitude, whose two ontological faces are materialism and idealism, are now plain to see: we are in the midst of what could very well be the Last Days as far as humans (and countless other species) are concerned. And the catastrophe is entirely of our own making.

Finding a way to believe in this world is not a metaphysical problem but an ethical one. Yet it is an ethical problem that requires us to think metaphysically about the nature of the universe. If we are to deal with it, we need to abandon our anthropocentrism. For me, this means first and foremost breaking away from the Cult of Pure Reason.*** We must open ourselves to more imaginal avenues of thought and experience. The imaginal is unconcerned with rational truth. It is concerned rather with visions that affirm creation, existence, nature, life and death, joy and terror. Spinoza, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Shestov, Whitehead, Bergson, Deleuze and Segall are just a few philosophers who have made it their task to affirm life and world rather than negate them with formulas such as “the world is mere X” or “life is nothing more than Y.” If we are to think our way through these troubling times, we could do worse than follow their lead.

Notes

* Panpsyche ("all-soul") could be translated, mythopoeically, as "Pan's Soul." For a beautiful exploration of Pan as personification of "nature within" and "nature without," see James Hillman's monograph Pan and the Nightmare.

** This does not imply that there is no God, only that God is not logically necessary—which, if you ask me, is how any self-respecting God would have it.

*** To quote Deleuze again, “It is not the slumber of reason that engenders monsters, but vigilant and insomniac rationality.” (Anti-Oedipus, 1977, 122)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed