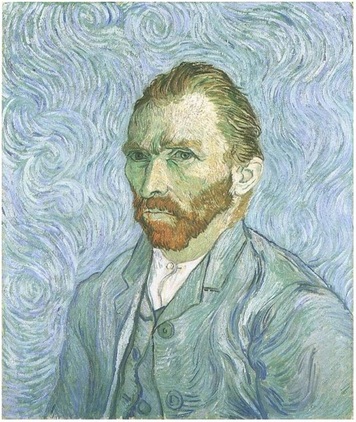

"...it's like discerning the different brush strokes that make up a painting and then concluding that the painter is composed of brush strokes!" - Bernardo Kastrup on "panpsychism"

"...it's like discerning the different brush strokes that make up a painting and then concluding that the painter is composed of brush strokes!" - Bernardo Kastrup on "panpsychism" So all I can do here is summarize my core argument, which remains implicit in my critique, as succinctly and as clearly as I can. I don’t expect Kastrup to change his views as a result, but maybe there are others who will be able to read me without presupposing the finality of their own conclusions and the superiority of their own intellects.

Here is the argument:

Consciousness as we know it presents itself as a subjective/objective phenomenon. We are conscious of ourselves, but experientially, we are only conscious of ourselves as subjective beings in an objective world. Discursive thinking splits this innately twofold phenomenon into completely separate and distinct conceptual entities: mind and matter. Materialists say that matter is “more real” than mind, and sometimes that only matter is real. Idealists say that mind is “more real” than matter, and sometimes that only mind is real. Both positions devalue or negate one aspect of a dyad without which consciousness would be inconceivable. Materialism and idealism are therefore equally "reductive." Each assumes an either-or situation when, in fact, experience presents us with a both-and situation that the human intellect cannot wrap itself around. In dismissing this puzzling situation as mere appearance and positing an underlying reality that is "really real," materialism and idealism inevitably concoct a transcendent order of being and slip it behind the phenomenal world of experience. That transcendent order is then tagged the one ontological reality while the phenomenal world is deemed "real" only in an epistemological sense. Anyone who is interested in knowing how this applies to Bernardo Kastrup’s philosophy is welcome to read or reread my original critique with the foregoing in mind.

I admit that I am no more of a metaphysical expert than Kastrup is. But I have studied metaphysics long enough to know that this discussion we’re having has been had many, many times in the past. Every conceivable idealist, dualist, and materialist argument has been adopted, and every position has been legitimately challenged. Time and time again. The reason, which modern physics makes amply clear, is that the real is innately paradoxical, weird, and unknowable from a human standpoint. This view is explicit in my book, where I argue that is is implicit in art. Art explores reality non-discursively, in such way as to preserve and bring to the fore its inherent and inexorable mystery. I could look for a passage to share here, but it so happens that Kastrup did the work for me in his response to my critique:

Go ahead and try to describe the underlying nature of reality without making any explicit or implicit reference of the notions of space and time. You will quickly realize that you can't, and for a simple reason: we cannot describe any pattern without laying this pattern out across a dimensional scaffolding. There is no pattern if there is no space-time. And if you can't talk of patterns, you cannot describe or articulate anything. You might as well shut up and stop bothering with philosophy. (my emphasis)

If I had to propose an alternative to Kastrup’s position, it would be something like, “There is no dreamer, there is only the dream.” I don't for a moment pretend that I could “prove” this discursively, since it specifically evokes a paradoxical, mysterious, weird world that no one will ever know intellectually. The mystery goes all the way down the dream. And to quote Shakespeare, who achieved greater heights (and depths) with poetry than any discursive thinker ever reached with propositional statements, the dream has no bottom.

In his books and essays, Bernardo Kastrup mounts a powerful assault against classical materialism. His work is full of brilliant insights, some of which I think resolve some of the more odious claims of traditional idealism. However, it remains in the end the exposition of a metaphysical system. As such, it supposes a capacity on the part of human intellect to penetrate the core of reality and explain it. I think this supposition is false. But then, just as Bernardo says he was able to overlook the mistakes he gleaned in my book, I'll gladly look past the glaring ones I sense in his writings in order to see his work as the elegant fiction that it is.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed