What I’d like to do is talk about how art can give us insights into the nature of consciousness, insights that may not be available to discursive modes of inquiry such as traditional science and philosophy. I should note from the outset that by “art,” I don’t mean just the visual arts but also music, cinema, theatre, dance, literature—all forms of artistic expression. I should also note that my intention isn’t to discuss the metaphysical views of this or that particular artist, although some of these will briefly come into play; rather, the focus here is on what the things artists create—the works of art themselves—tell us about the nature of mind and matter, self and world, regardless of their authors’ personal beliefs. There is, I believe, a metaphysics that art as a medium endorses whenever its deployment results in a genuine artwork. In McLuhanian terms I am asking the question: What is the message of the medium of art with regards to the nature of consciousness?

Unlike science and philosophy as commonly practiced, art isn’t discursive. Artistic expression isn’t an attempt to represent reality as it might appear “objectively” to a pure intellect. On the contrary, artistic expression captures something in reality while preserving the artist’s intimate, direct experience of it. Works of art include the experiential dimension, everything we normally associate with “consciousness.”

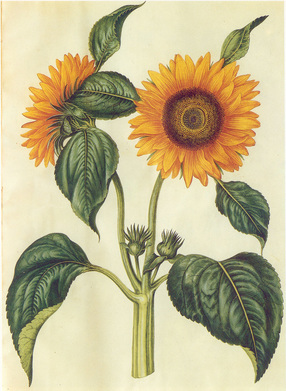

In this painting, something familiar is reimaged in light of an ineffable newness that inhabits it and makes it an event. We suddenly see that there was never any such thing as “sunflowers” in the abstract, but only this event that the intellect classifies under a fixed concept, which for its part exists only in and for the intellect. In Reclaiming Art, I write: “Whereas the [botanical] diagram eliminates every anomaly in order to represent the abstract specimen, the painting eliminates all that is general in order to conserve only the anomaly. In other words art isn’t after the ideal model of a thing but its immediate manifestation, which is all that truly exists, experientially speaking.”

As an aesthetic enterprise, then, art isn’t concerned with the conceptual representation of the world. The aesthetic does not deal with concepts but with direct sensations or “affects.” The aesthetic defines an engagement with reality at the preconceptual level of instinct and intuition. Van Gogh’s picture conveys the sunflower as a pure sensation—that is, the sunflower as it appears prior to any conceptualization. That’s what makes it art and not botany.

This isn’t to say that aesthetic vision is unable to perceive concepts or merely dismisses them as false. Novels, poetry, and even music are full of concepts—by which I mean notions, ideas and beliefs. But when such things appear in a work of art, they appear as sensuous events within the aesthetic world that the work evokes: they are on a plane with everything else. Take, for example, the idea of Christianity in Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov. What is it that makes this novel, the work of a fervent Christian, different from those fundamentalist paperbacks you find at the drugstore? It is that The Brothers Karamazov doesn’t reify Christianity; it doesn’t raise it above the fictional universe of the novel to make it a “given” upon which the meaning of the story hinges. On the contrary, Dostoyevsky allows his Christianity to exist on a plane with the other forces that compose his book’s aesthetic universe.

At the sensuous level of aesthetic experience, all things—even ideas, notions and beliefs—appear as forces. It was Friedrich Nietzsche who showed us that even the most abstract concepts are, at bottom, sensations in disguise. This, anyway, is how concepts appear in the aesthetic vision. They have no transcendent intellectual value. They are not outside the world looking down on it. They are not “objective.” They are, like all things, events in a world. One uses concepts as one might use a hammer or a brick, to make something or destroy it. Judging from the novels he wrote, Dostoyevsky didn’t see Christianity as a theory to be accepted as “true” or rejected as “false”: he saw it as a force that inhabits us, opening up new possibilities and closing off others—a force that belongs to this pre-conceptual world—what Jung might have called an archetype. The same view is present in Nietzsche’s great poetic work. Nietzsche was above all a great aesthetic thinker (perhaps the greatest aesthetic thinker who ever lived), and his deepest insight was that there is only one reality shaping the world: the energy he called will-to-power. Look at any concept closely enough, he said, and you’ll see that behind it burns a sensuous force, a will-to-power.

Remove everything that has no relevance to the story. If you say in the first chapter that there is a rifle hanging on the wall, in the second or third chapter it absolutely must go off. If it's not going to be fired, it shouldn't be hanging there.

When Chekhov advises writers to “remove everything that has no relevance,” he is saying that each of the elements that compose a work of narrative art must enter into a meaningful relation with the work as a whole. Every element is the expression of a force, something that conditions and drives the living world of which it is part. The rifle on the wall is never “just” a rifle on the wall; it is a will, an intention, a desire which, at some point, must burn: in art, guns want to go off. In Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, the Overlook Hotel is a living creature, a full-fledged “character” with at least as much agency as the hapless family living in its bowels. In Dickens’ Great Expectations, the foggy moors, Miss Havisham’s rambling mansion and the city of London all exert a presence that makes them more than mere backdrops for the actions of the human characters: rather, the characters are themselves expressions of these places, which are every bit as alive and ensouled as any human being, if not more so on account of their vast proportions.

Artists are people who can look at the world aesthetically, at the level of sensation—the level of forces. They experience matter as alive and vibrant. Life, in its broadest sense, ceases to be the property of conscious subjects or even organic creatures in order to become the essence of nature itself, the energy coursing through all things. And by “all things” here, I don’t mean static objects but events, every one of which is related to every other one, and all of which exist only by virtue of those relations. The work of art shows us the world as a clash of forces, an agon radiating a strange, animistic vitality or an “inorganic life,” to borrow a term from Gilles Deleuze, which defines the Real.

The American philosopher Susanne Langer wrote: “Art is the objectification of feeling and the subjectification of nature.” In art, everything the human mind normally deems the exclusive property of human subjectivity is restored to the forces that compose a pre-human aesthetic world. All that ordinary human awareness deems to be mere objects or things is also restored to those forces. There is only the clash, the agon, the event that is a kind of miracle happening at each moment. Art captures the moment in order to preserve the miracle.

Under the terms of ordinary personal awareness, steered as it is by the concept of subject and object, it may seem that the experience of, say, a vase of sunflowers belongs to us, that is, that we are the basis upon which such an event could be called an experience. But when Van Gogh sees a vase of sunflowers, he experiences it as belonging to something bigger than his subjective mind. This “something” is what Jean-Paul Sartre called a transcendental field, a kind of proto-consciousness in which beings arise as subjects and objects. Deleuze defined the transcendental field as “a pre-reflexive impersonal consciousness, a qualitative consciousness without a self.” (Deleuze, Pure Immanence: A Life)

It is this field, which I call simply the Real, that produces Van Gogh as a subject and the sunflowers as an object at exactly the same moment. And it is this field that is captured in the painting, which includes, on a single plane, both the content of the experience and the act of experiencing. Because Van Gogh stayed true to the transcendental field, because he allowed his own subjectivity to be folded back into the event that he was trying to capture, he produced a work that we cannot dismiss as just another object. The painting is alive, the sunflowers are alive—the life and agency we normally attribute only to ourselves is present in them. We can’t in good faith say that the sunflowers are merely objects of our perception unless we are also ready to admit that we are the object of their perception, because the sunflowers here are subjects in their own right, watching us watch them. In short, the transcendental field is not the property of the perceiving subject but the impersonal space in which both subject and object arise as the twin poles of an unprecedented event. Paul Cézanne evoked this beautifully when he said that, in the heat of creation, he and the landscape he paints constitute “an iridescent chaos.”

Perception can be uncoupled from subjective consciousness. There is a pre-subjective perception; it is the weird awareness of a transcendental field, “a qualitative consciousness without a self.” The iridescent chaos that Cézanne talks about is a perceiving chaos; it is in some inhuman fashion aware. Nietzsche: “And when you gaze long into an abyss the abyss also gazes into you.”

When we imagine that it is the forces that shape the universe that perceive, and not the subjective minds that inhabit the universe, we are close, I think, to what aesthetic vision is telling us through art. The metaphysics endorsed by the medium of art amounts to a form of animism or panpsychism. Art confront us with a panpsychic universe: a universe that exists for itself, objectively, just like the material cosmos of the scientists, but whose integral sentience produces subjectivity all over the place.

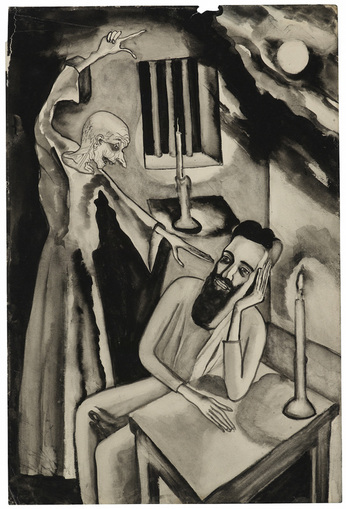

Matter is physical, matter is psychic: both statements are true, but only when said together. As soon as one is used to negate the other, as we see in the case of materialism or idealism, the aesthetic vision is lost: concepts are placed above the sensations that form them, the human world is raised above nature, and we are inevitably left with some manner of anthropocentrism. The panpsychism of art, in contrast, entails that human consciousness is just one manifestation of a proto-consciousness that precedes all human conceptualization. The Real is not a comfortable theatre for human action but an alien place—strange, uncanny, or to borrow a term from weird literature, eldritch. The pessimistic philosopher Eugene Thacker, in a brilliant analysis of Fritz Leiber’s horror tale "Black Gondolier,” describes a moment where “everything human is revealed to be only one instance of the unhuman.”

We have all experienced this kind of thing before, be it in particular rooms, in old houses, out in nature, or in some derelict urban area: a presence that precedes and exceeds us, that perceives us even as we perceive it, a strange form of life that isn’t reducible to our own minds but points us rather to an alien psyche undergirding the familiar world. There is nothing comfortable or homely about this presence; indeed at times it verges on the terrifying. Facing it means confronting the “it” that shapes all things, even the most familiar ones, even a couple of empty rooms, even the eyes and brain with which I perceive those empty rooms.

Hammershoi’s painting offers a glimpse of this occluded reality. When we allow ourselves to really see the painting, there is always the chance that its vision stays with us afterwards. Who hasn’t experienced a film, play or concert so powerful that for hours or even days afterwards, it seemed to reimage the real world? We are all artists when this happens, we are all seers gazing beyond the ambit of our closed, anthropocentric subjectivity. What disappears in such moments is judgement—the judgement that accompanies all conceptual thinking when it reduces things to mere objects that exist for us.

Oscar Wilde famously wrote, “All art is quite useless.” What he meant, perhaps, is that the purely aesthetic nature of the work of art allows us to see the ultimate uselessness of everything. By which I mean that art allows us to see things for what they are in and for themselves instead of seeing only the uses we can put them to. To see the world aesthetically is to see beyond the judgements of self, culture, and society. For insofar art belongs to the realm of dream and vision, it is not part of culture; on the contrary, it is the intrusion of nature into the cultural sphere. And what its intrusion reveals, ultimately, is that in fact there never was “culture.” Words, concepts, beliefs, ideations exist only as forces in a world of forces. Again: “Everything human is revealed to be only one instance of the unhuman.” It was Paul Klee who said that art has the power to make us realize that we humans are not the masters of the universe, that each of us is “a creature on the earth and a creature within the whole, that is to say, a creature on a star among stars.” (source) To see things otherwise is to judge the world, to arrogate the right to decide on the purpose and nature of things which, in reality, exceed our powers of judgement. Even in a statement as inoffensive as “a cat is just a cat,” there is a reduction of a strange, vast, unknowable nature to what Shakespeare called our “little world of man.”

But if we look closer at the image on the wall, we see that it depicts the Day of Judgement from the Book of Revelation. Now, you’d think that someone who took the last chapter of the biblical drama seriously would find better things to do with their time than weighing gold and pearls. But so long as we remain possessed by the spirit of judgement, it is impossible to see Revelation for what it really is: not a judgement of the mortal kind, but an unveiling—an apocalypse—in which things are revealed in their terrible, unhuman suchness. Apprehended as an aesthetic event, the Last Judgement resembles what William S. Burroughs called the Naked Lunch, that “frozen moment where everyone sees what is on the end of every fork.” (Naked Lunch, preface) But in the moment captured by the painting, the Last Judgement is the last thing on the woman’s mind. Right now she seems convinced that her “little world of man” really is the whole picture, or at any rate that it is close enough to the whole picture to allow her to draw some definite conclusions as to what means what in life. She doesn’t seem to see the pearls, the scales, the sunlight, the oil painting, even her own body for what they are: miraculous events, unprecedented explosions of the new—terrible, beautiful, and real.

Vermeer’s painting, however, shows us all this even as it reveals the act of judgement that denies it. Looking closely, we see that the woman’s scales are empty, that in fact she is weighing nothing but the transience of the moment itself.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed