The year-and-a-third since Reclaiming Art was released has been a trip. For one, I've made a lot of new friends. I've also discovered that the preoccupations which led me to write the book are shared by many. The Spanish edition heralds the beginning of a new chapter in the life of the book, connecting it with a new readership.

In other news, Metapsychosis, a new and ambitious literary venture spearheaded by my brothers-in-arms Marco Morelli, Jeremy Johnson and Natalie Bantz was officially launched yesterday. For the occasion, Jeremy penned a beautiful editor's letter and Marco released a galvanizing video monologue that plays like a genuine sorcerous invocation. As a member of the creative team, I've had the chance to peruse the content that will grace the interface of the journal in its inceptive phase. It's going to be something. And I'm not just saying that because I have a piece appearing in it, although that is also true.

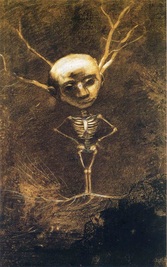

The first of Metaphsychosis's offerings include a marvellous new poem by the great William Irwin Thompson entitled "Four in the Morning." It is, in my opinion, one the clearest distillations of weird realism I've come across. That it conveys the atmosphere of a nightmare is entirely appropriate. Four a.m. is the end of the Witching Hour. The witch-wind has blown through the room and one is left to ponder what just happened in the predawn dark. This is the hour that gives the lie to every philosophical system, intellectual model, and expert opinion. It unveils a reality no brain-shaped box can contain. Four a.m. does not call for the old anthropic hubris but for something else, a form of courageous humility, a willingness to concede to the forces that teem around us unseen all of the autonomy, self-existence, and agency which we as a species would prefer to claim for ourselves alone. As Dr. Bill puts it at the end of Eyes Wide Shut: "No dream is ever just a dream."

RSS Feed

RSS Feed